‘Subpoenas are necessary’: House watchdog details extensive meddling with CDC Covid-19 reports

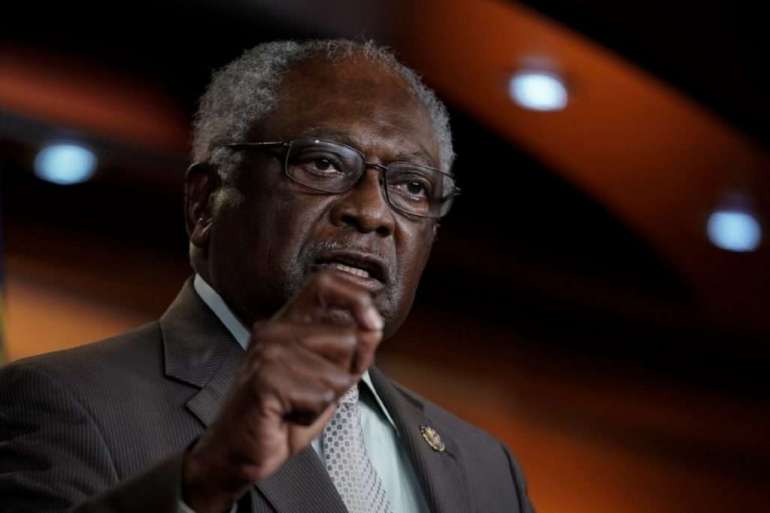

Clyburn issued subpoenas to Azar and Redfield, ordering them by Dec. 30 to produce “full and unredacted” documents that Clyburn said his panel has sought for months.

The panel’s probe into administration’s coronavirus response began in mid-September, shortly after a POLITICO story revealed how appointees meddled with the famed Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports, which are authored by career scientists and are typically free of political interference. In recent weeks, the panel released evidence alleging that Redfield ordered agency staff to delete an email that appeared to show political interference and that a political adviser repeatedly advocated a controversial “herd immunity” strategy regarded by most public health experts as reckless.

Clyburn’s subcommittee on Monday produced dozens of new documents detailing how Trump appointees — including then-science adviser Paul Alexander, the department’s top spokesperson Michael Caputo and other health department officials — worked to subvert the CDC’s MMWR reports.

Among the MMWRs that were targeted for edits: reports on the use of masks, the spread of Covid-19 in children, the virus’ transmission during an April 7 primary election in Milwaukee and other reports that were seen as politically sensitive.

The newly released documents further detailed appointees’ extensive efforts to suppress and even write a rebuttal to planned reports on hydroxychloroquine, the malaria drug favored by President Donald Trump as a coronavirus treatment despite little evidence of its effectiveness. CDC has historically insisted that political appointees not review the draft content of the MMWRs, but in at least one case, Trump appointees obtained the full text of a pending report.

“I got the draft of the WWMR [sic] about hydroxychloroquine and media that was supposed to be released on Tuesday,” then-CDC adviser Nina Witkofsky wrote on June 29 to Alexander, Caputo and Caputo’s aide Madeleine Hubbard. Witkofsky, who served as a contractor helping plan events for Medicaid chief Seema Verma before joining the Trump administration this summer, was tapped in August to be the CDC’s acting chief of staff.

The MMWR on hydroxychloroquine, which reviewed how doctors prescribed the drug, was originally scheduled to be published on June 30 but was not published until Sept. 4.

The reasons for the delay were not immediately clear, but Trump appointees in the meantime further strategized on how to minimize the CDC’s findings – including Alexander’s plans to publicly dismiss the agency’s hydroxychloroquine report. “The authors of this study are a disgrace to public service,” Alexander wrote in a planned rebuttal that does not appear to have been publicly released.

In his letter to HHS, Clyburn said the department continues to block his panel’s scheduled interviews with Redfield, CDC principal deputy director Anne Schuchat and Witkofsky, among other officials that HHS previously agreed to make available. HHS also waited until after the election to release its documents, which were mostly pulled from Alexander’s files, Clyburn wrote, rather than from officials like Azar and Caputo despite a previous commitment to do so.

“Given the importance of the Select Subcommittee’s investigation and the continued obstruction by HHS, subpoenas are necessary,” Clyburn wrote.

Asked about the House panel’s findings, HHS said that it had pulled more than 1 million documents for the subcommittee’s probe and that Alexander, who has since left the department, did not set strategy.

“While the Administration is focused on vaccination shots, the Subcommittee is focused on cheap shots to create headlines and mislead the American people,” said HHS spokesperson Caitlin Oakley.

HHS did not respond to a question about whether the department would comply with the panel’s subpoena. CDC did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Alexander and Witkofsky did not immediately respond to requests for comment. Caputo, who took medical leave the same day that Alexander left the department in September, has referred previous inquiries to HHS.

According to the new documents, Bill Hall, the top career civil servant in the HHS press shop, on June 5 warned Alexander, Caputo and other officials that they should not interfere with the MMWRs, comparing the CDC’s flagship reports to a “peer-reviewed journal” akin to the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“[A]s matter of long-standing policy, we do not engage in clearing scientific articles, as that arena needs to remain an independent process,” Hall wrote in an email obtained by the subcommittee.

But the subcommittee’s documents reveal that political appointees instead kept trying to edit a series of internal and external reports.

“Hi Michael, is this not the article we were shelving?” Alexander wrote to Caputo and Witkofsky on June 29 about a pending CDC-authored report on hydroxychloroquine that was set to run in JAMA. The House panel concluded that Alexander “appeared to mistake” the planned JAMA report for the MMWR report that would be delayed.

The subcommittee also released documents showing how Alexander repeatedly petitioned Charlotte Kent, the MMWR editor-in-chief, to make changes to planned reports, such as an upcoming MMWR on the spread of Covid-19 at a Georgia summer camp amid a robust debate about whether it was safe to reopen schools in the fall. In a separate email chain, CDC career officials discussed how best to navigate the political pressures, and Kent ultimately sent Alexander an email seeking to placate him.

“In response to thoughtful comments from CDC leadership and you, the opening sentence of Georgia’s report has been reframed,” Kent wrote to Alexander and other officials on July 28. “The opening sentence was the only reference to schools or institutions of higher learning in the report, and reference to them has been removed.”

However, the Georgia summer camp report, which was released on July 31, still angered the health department’s Trump appointees, sparking another effort to author their own response that they believed would be more favorable to the president.

“I am not sure where it can be published but this has very re-assuring information and even for the White House,” Alexander wrote in a planned rebuttal to the report.

HHS has insisted that there was no interference in the MMWRs, pointing to comments from Kent, the reports’ editor, who during a Dec. 7 interview with House investigators said that the agency published reports that were scientifically sound.

“Dr. Kent’s interview established there was no political interference in the publication of MMWR Articles,” Sarah Arbes, the HHS assistant secretary for legislation, wrote to Clyburn last week.

Clyburn, however, said Kent’s testimony made clear there was political pressure to alter her office’s reports.

“To the extent career staff were successful in limiting the damage, as Dr. Kent stated she was, that is a testament to the career staff’s integrity and resilience — not an indication that the Trump Administration’s political pressure tactics were appropriate or scientifically sound,” Clyburn wrote Monday.

The documents released by Clyburn’s panel also further shed light on interactions between Trump appointees and career health department officials as the outbreak worsened. In one exchange, a CDC official complaining about the “pattern of hostile and threatening behavior” from Caputo, the department’s top spokesperson who was personally installed by the president.

“In what world did you think it was your job to announce an Administration public service announcement to CNN?” Caputo wrote to a CDC official who confirmed to a CNN reporter in June that the health department was pursuing a vaccine education campaign. Caputo had previously told the reporter she was “wildly incorrect” when she inquired about the campaign.

In another set of July emails, Caputo demanded the name of a CDC press officer who arranged an interview between a senior official and NPR about the health department’s data changes without his permission.

After POLITICO obtained emails of Alexander pressuring infectious-disease expert Anthony Fauci to not speak publicly about the risks of Covid-19 to children, Alexander protested to colleagues that he wanted to go public with his complaints about Fauci.

“They have no clue what they are saying and I welcome the chance to inform them,” Alexander wrote on Sept. 9. HHS announced that Alexander, who is a part-time professor at a Canadian university, would exit the department a week later.