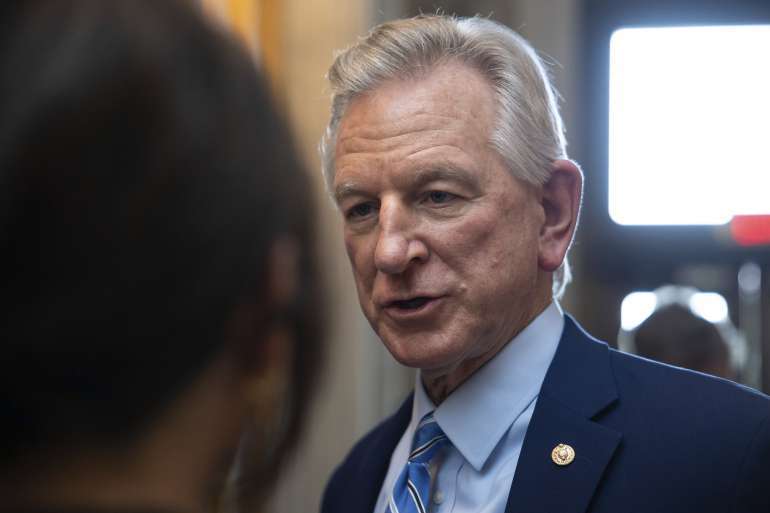

How Tuberville’s blockade of Pentagon nominees could end

“Normally, a Republican on the Armed Services Committee can see the big picture, that if even our national security becomes subject to the culture wars, then that’s bad for the country,” Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) said. “But, you know, his superpower is shamelessness.”

A spokesperson for Tuberville said that there’s been “no movement” on the dispute, but said Tuberville spoke on the floor last week with top Senate Armed Services Republican Roger Wicker (Miss.) “and they agreed to have a conversation about it later.”

The Senate recessed last week without resolving the stalemate, but there are several scenarios that could play out when lawmakers return. But none of them is easy, or one would’ve happened already.

1. Tuberville gets an NDAA vote

Senate Armed Services Chair Jack Reed (D-R.I.) has said Tuberville should take the more straightforward path of seeking an amendment vote on the Pentagon travel policy via the National Defense Authorization Act, the Pentagon’s annual policy bill. It’s not a great deal for either side, but it’s probably the most likely one.

“My instinct would be that he’s going to have to get a vote,” said former Senate Armed Services staff director Arnold Punaro. “He would certainly have that opportunity in the markup. And he’ll have to decide based on that outcome, whether he continues … and he’ll have another shot at the floor.”

One predictor of how that might go is a Senate measure Tuberville led last month to scrap abortion care at the Department of Veterans Affairs, which failed mostly along party lines, 48-51. Senate Armed Services Democrat Joe Manchin (W.Va.), a co-sponsor of the bill, voted in favor, while Sens. Susan Collins (R-Maine) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) voted against.

The problem: The NDAA is at best a moving target. Even if a vote in SASC’s closed-door markup would satisfy Tuberville, the markup has been delayed already to accommodate debt ceiling talks. If Tuberville wants a floor vote, it’s a gamble whether there will even be one, since the Senate hasn’t taken up its own version of the NDAA in years.

A complication for Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer is whether he’d be forcing a tough vote on vulnerable Democrats and whether enough of them would defect for Tuberville to actually win.

2. Voting one-by-one on promotions

Technically, the block isn’t a block. It’s more of a delay that forces extra votes for each nominee. So Schumer could get around Tuberville’s hold by filing cloture and cutting off debate on each nominee, which requires an extra procedural vote and more floor time. This is the case with virtually all of President Joe Biden’s judicial nominees and most senior picks.

Tuberville himself has noted that he’s really just forcing the Senate to take roll call votes. So if the Pentagon is facing vacancies at its highest levels in the coming months as members of the Joint Chiefs retire — and their replacements face confirmation — Schumer could file cloture and schedule some one-by-one votes to avoid gaps at DoD.

The problem: Despite his argument, the Senate can’t realistically vote on each of the hundreds of general and flag officer promotions expected this year, or it would have time for nothing else.

Filing cloture on a military promotion is also a cave that Schumer would likely want to avoid, as it would allow Tuberville to claim validation that he isn’t truly blocking anyone’s confirmation despite the impracticality of holding votes on so many nominees. And it would have the effect of politicizing promotions, Punaro argued, normalizing delaying them for partisan gain.

“The minute we just do the first cloture for a military nomination, we have now turned military nominations into federal judges,” Punaro said. “We will never get it back. We will totally politicize the military.”

3. GOP leaders intervene

Republican Leader Mitch McConnell could privately convince Tuberville to quit or compromise, using his influence or leverage. It’s a scenario Democrats pressed for even before McConnell said he doesn’t support Tuberville’s actions.

The problem: Would Tuberville listen? When McConnell told reporters this month, “No, I don’t support putting a hold on military nominations,” it had no discernible effect and Tuberville dismissed it, saying, “Everybody’s got their opinion.”

Not all GOP leaders agree with McConnell. One McConnell ally, Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), told reporters the opposition is warranted — “One of the biggest problems around here is people aren’t held accountable when they overstep their authority” — and McConnell counselor and Senate Armed Services member Deb Fischer (R-Neb.) said private pressure isn’t how this works.

“I don’t believe I have ever heard of the Republican leaders pulling a Republican senator aside to have a talking to — never,” she said.

4. The Pentagon caves

Facing a personnel crisis in the military’s highest rungs if the blockade continues, Austin could give in to Tuberville and rescind the policies he issued this year, which cover travel costs and permit leave for troops who must travel to obtain abortions and other reproductive health procedures.

The problem: The Pentagon is unlikely to cave because it could incentivize future holds to reverse controversial policies. Plus, Democrats who have rallied against Tuberville’s tactics and in favor of abortion rights would be furious.

It also would reverse a policy that Austin has publicly defended on Capitol Hill. Faced with GOP arguments that the Pentagon is undercutting laws that bar funding for abortion, Austin has told lawmakers his policy is on firm legal footing and argued it’s important to ensure reproductive health access for women in the military.

“About one in five of our troops are women,” Austin said at a May 11 Senate hearing. “I want them focused on the mission and not worried about whether or not they’re going to have access to reproductive health care.”

5. Space Command wildcard

Tuberville’s freezing out military nominees over abortion is playing out as his state is fighting to become the permanent home to the new U.S. Space Command amid speculation that reproductive rights could play a role in that major basing decision.

Huntsville’s Redstone Arsenal was chosen in the final days of then-President Donald Trump’s term. But lawmakers from Colorado, where Space Command is temporarily located, have clamored for the Biden administration to undo the move, arguing it was driven by political favoritism.

Alabama Republicans have cited reports that the Space Command move could be blocked over Alabama’s abortion laws, which are some of the country’s most stringent.

The two issues aren’t directly linked, at least publicly, but the Space Command and abortion debates have overlapped and feature some of the same antagonists. Colorado Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet is one of Tuberville’s top critics on the military abortion debate. Bennet has pushed to confirm promotions several times on the Senate floor, while separately working to keep the space cadre in his state.

The problem: Many of the combatants have been careful not to mix the two fights publicly, wary of supercharging two already politically charged issues.

Colorado’s delegation, which includes several Republicans, is arguing Space Command’s operations will be set back by moving across the country. Still, Alabama Republicans such as House Armed Services Chair Mike Rogers have pointed to the abortion issue as evidence of “politically motivated interference” by the Biden team.

Pentagon and Air Force leadership have been tight-lipped about the decision, which was supposed to come months ago. But if the administration elects to keep the command in Colorado, it could delay a final announcement until after the nominee dispute is resolved to avoid compounding the standoff and risk a response from the rest of Alabama’s delegation.

A version of this story previously appeared in POLITICO Pro’s Morning Defense.