HIV infections drop, but racial gaps remain

Progress was also uneven among racial groups, demonstrating that barriers remain to people of color accessing testing and treatment. While white gay and bisexual men between ages 13-24 saw a 45 percent drop in infections, it was just 36 percent for Latinos and 27 percent for Black men.

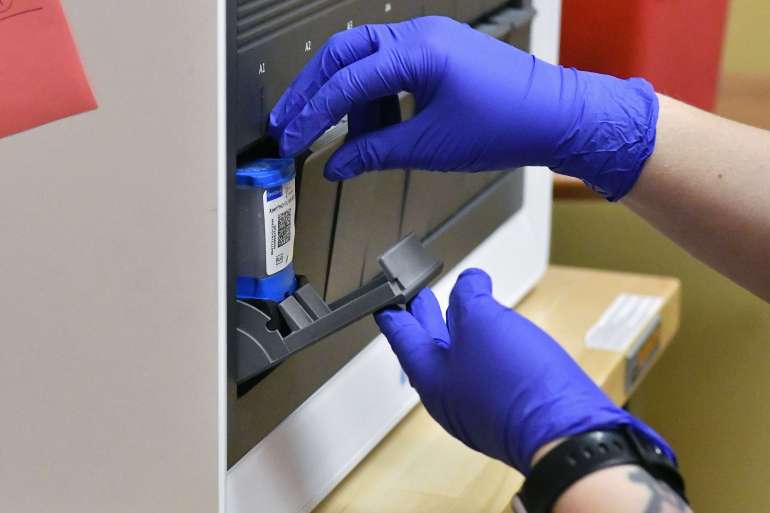

A big driver of that disparity, the CDC found, was access to HIV prevention medication, known as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, which is highly effective at blocking transmission of the virus.

Overall progress on getting PrEP to people who could benefit from it was significant, with uptake surging from 13 percent in 2017 to 30 percent in 2021. But there’s a wide gap between the 78 percent of white people in that category taking the medication versus 21 percent of Latinos and 11 percent of Black people.

Health officials said they will soon roll out plans to narrow these gaps, including one PSA campaign in the South focused on Black and Latino men who have sex with men and another encouraging medical providers to prescribe PrEP to more at-risk Black women.

Still, pandemic disruptions to the medical system have knocked the U.S. off track to meeting Ending the HIV Epidemic goals set during the Trump administration, and despite marked progress, many challenges remain.

More than half of new HIV infections in 2021 were in the South, where more states have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and where officials are moving aggressively to remove people from Medicaid rolls if they can’t confirm their eligibility.

And a yet-to-be-finalized debt ceiling deal between Democrats and Republicans could mean tens of billions of dollars of cuts to public health funding for testing, case investigation and treatment of HIV and other STDs.

“This will result in new infections, more people living with HIV and the need to provide lifetime care and treatment,” warned Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute.

And because having another STD like syphilis or chlamydia significantly raises a person’s risk of contracting HIV, federal health officials argue that the budget cuts would have a spillover effect.

“We’re not going to end the HIV epidemic unless we address the [sexually-transmitted infection] crisis in this country,” said Harold Phillips, who leads the Office of National AIDS Policy and sits on the White House’s Domestic Policy Council.

Additionally, a case pending in federal court could eliminate Obamacare’s mandate that insurance companies cover PrEP medication — and other preventive services — at no cost to patients.

Though he declined to comment on the litigation, Mermin said he’s concerned “about any situation that makes it harder for people to get highly effective HIV treatment and prevention services, which we know from our data are not reaching everyone who could benefit.”

Other barriers to access are more nuanced, he and other health officials noted.

Mermin cited “age-old” challenges of “poverty, differences in geographical access, racism, discrimination, homophobia and stigma,” while Demetre Daskalakis, director of the division of HIV prevention at the CDC, warned the wave of new laws in GOP-led states targeting gay and trans youth could make those populations more distrustful of the government and less likely to seek services during future disease outbreaks and health emergencies.

“When you send the message to people that you don’t care about their lives, it’s then hard to convince them that you care about their lives,” he told POLITICO in an interview.